Browders’ tale shows resilience of city, it’s residents

Several years ago, I was working on a story about the creation of the first schools in Boulder City and in our local library came across the incredible oral histories collected and transcribed by former Boulder City/Hoover Dam Museum Director Dennis McBride.

The detailed accounts of early settlers bravely pulling up stakes and coming to this bleak desert outpost during the Great Depression, an economic crisis that was having reverberations around the world, were captivating. After a page or two, I was hooked.

What struck me was not only the courage and resilience of the men risking their lives building the mammoth slice of concrete known as Boulder Dam, but the strength of the families they brought with them. Wives and children, for example, who had to leave their homes and build a new life in a place that must have felt like the edge of the world.

In 2009, I started setting up interviews with a handful of those children, most of them in their 70s and 80s at the time. They included local pioneers such as the Godbey sisters, Laura and Ila; Alice Dodge Brumage; and Leonard Stubbs.

I thought I could transcribe the interviews and donate them to the newly created 31ers Educational Outreach Program, or maybe even write a book.

To be honest, I simply wanted to hear more stories and knew there would be something special about getting the perspectives of the youngest settlers.

One of those early residents and her stories have been on my mind a lot lately. In 2012, I talked to Ida Browder Kelley, the daughter of Ida Browder, who opened the first private restaurant in 1931 to feed the men who were flocking here for work.

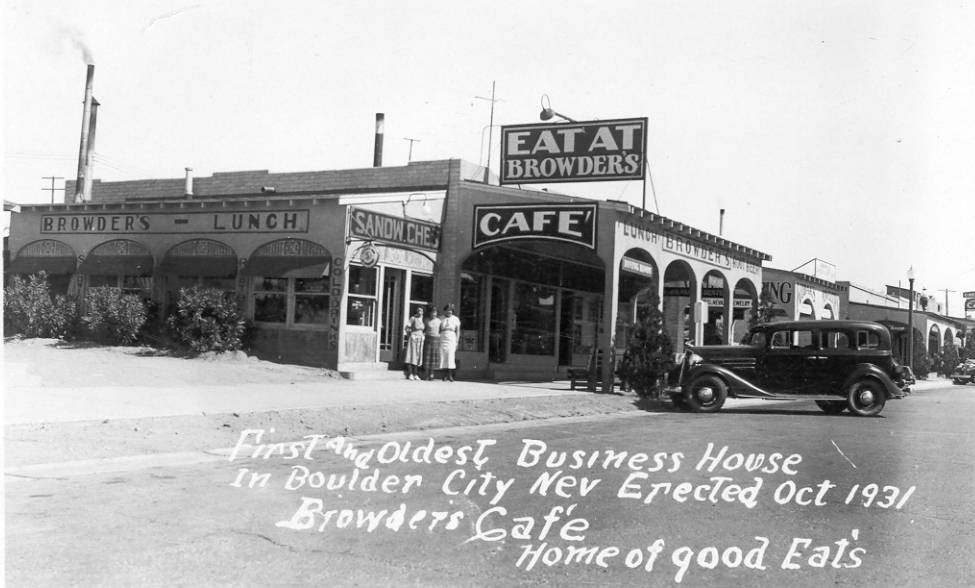

The downtown Browder building, including the original diner fronted by its telltale archways and considered the oldest commercial structure in town, has been sitting empty for several months as the current owner decides whether to sell the historic building, find a new purpose for it or tear it down.

I don’t know what the future holds. I do know that human nature has a way of making us nostalgic for the things we might lose. Perhaps that’s why Kelley and her stories keep floating to the surface when I see that building at Nevada Way and Ash Street.

Kelley was 89 and living in California when we had our phone conversations. Her memories of living here as a child came easily, like unspooling thread. She told me it all started when her newly widowed mother, needing a way to support the family, heard about the dam project and decided it was the rare opportunity to make a living during otherwise desperate times.

She got permission from the government to build a diner on the federally run Boulder City settlement — a rare win for a woman on her own — and in the summer of 1931, Kelley, her mother and older brother left their home in Salt Lake City for the Nevada desert.

In the beginning, they lived in a tent just behind the diner’s construction site. Kelley was 8 years old. The tent was stacked with boxes of restaurant equipment she had to maneuver around, and their only water supply was stored in a barrel outside.

Pelting dust storms got so bad that once, when the tent was locked up and no one was home, she crawled into her adopted stray’s doghouse with him and waited it out.

By Christmas of 1931, the diner was ready for business. It quickly proved its usefulness as work on the dam moved forward at a feverish pace, and there was a time when it stayed open 24 hours a day.

The younger Ida was quite a fixture at Browder’s Cafe. If one of the waitresses or cooks didn’t show up, she had to take their place. She learned how to balance six heavy cups of coffee in her left hand and put them all down on a table without spilling a drop, she told me.

The dam workers treated her like a kid sister and now and then gave her gifts such as a pair of wooden stilts or a piece of driftwood with “Boulder Dam 1931” carved into it. In fact, when I talked to her in 2012, she still had that piece of driftwood after 80 years.

Customers had nicknames like “Shorty” or “Smitty,” she told me, but she never asked them their real names because that was against the “Code of the West.” And if a man passing through town was down on his luck and had a belly to fill, he knew to go to Browder’s Cafe because, at the very least, “Mama Browder” would give him bread and butter and a big bowl of soup.

According to Kelley, they would pay in kind with pictures they painted on rocks and pieces of cardboard, trinkets that dotted the Browders’ tiny apartment behind the restaurant because her mom liked to look at them.

Mrs. Browder, as she was often called, is a story unto herself. She was an Austrian countess who grew up in a home with servants, knew five languages and loved opera. Yet, there was a strength and independence that could make her come across like a bull in a china shop.

According to her daughter, she once fired a warning shot at a customer because he kept forgetting to turn off the syrup spigot in her root beer stand next to the cafe.

She was also ahead of her time in many ways. One of my favorite stories surrounds the tiny lookout room that still pokes up from the top of the Browder building on its southwest end. The elder Browder had it built as a study room for her daughter but made sure it had windows so she could look up from her books now and then.

“She said … ‘I want you to look out at the desert and appreciate the beauty of it. There’s beauty everywhere if you look for it,’” Kelley said.

Whatever the fate of the Browder building, my hope is that the stories live on. Pioneers like Ida Browder, Ida Browder Kelley and all the others keep us looking not just to the past but to the courage of those who brought us to this point and to what’s possible even in the worst of times.

Joan is a local freelance writer/editor and onetime volunteer with the 31ers Educational Outreach Program.