Last known Hoover Dam worker dies

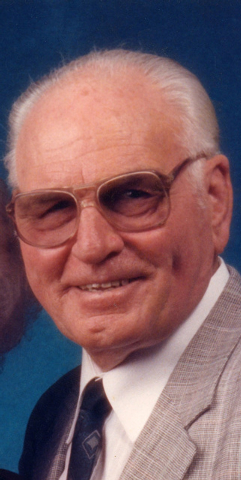

Darwin Colby, the last remaining worker from the Hoover Dam project, according to museum records, died last week, closing the book on a legacy written more than 80 years ago by thousands of men desperate to make a living during the Great Depression.

Colby, 98, died in his sleep in the early hours of Nov. 12. Born and raised in the small town of Salina, Utah, located about two hours south of Salt Lake City, Colby was 15 years old when he found out about the Hoover Dam project from his brother-in-law, Verl Miner.

“He (Verl Miner) sent word back to Utah and told him that after he graduated high school (he needed) to get his behind down here,” Colby’s nephew Gary Miner said. “It was a good job. He got on his motorcycle and drove out here.”

The drive to Boulder City gave Colby the chance to land a job on the dam during the toughest economic chapter in American history. It also allowed him to get out of Salina, which had a population of less than 1,500 at the time, according to the 1930 U.S. Census.

“Being raised on a farm, they had to grow their own food because there was no money to buy anything. He didn’t want to live like that in the Depression,” Colby’s daughter, Cathy Leonard, said.

Shirl Naegle, an employee at the Boulder City/Hoover Dam Museum, said Colby’s death not only signifies the last of the “31ers,” it signifies the end of a generation that worked tirelessly in unbearable conditions to make such a paramount project possible.

“It’s not only significant for the physical structure they built, but I think there’s also a legacy to the American ‘can-do’ sort of thing,” he said. “There was this recognition that this was not just another dam being built in the West. The workers understood that. There was a feeling of accomplishment.”

During his time at the dam, Colby worked on the bypass valves and did concrete work on the spillways. After those jobs were completed, Colby was laid off like several other workers. But Gary Miner said his uncle didn’t go down without a fight.

As the story goes, according to Miner, Colby spoke with Chief Engineer Frank Crowe in the mess hall after he was laid off. Colby was persistent in wanting to keep working and told Crowe he wanted to stay on the project. After hearing him out, Crowe gave Colby the green light, and he stayed on until the dam was completed in 1935.

In December 1935, Colby enlisted in the Navy where he held the post of airman first class. Shortly after an honorable discharge, he worked in the shipyards of Oakland, Calif., during World War II. He returned to Utah after the war, where he worked in a mortuary in Salt Lake City.

Colby bounced between Utah and Northern California, but his heart was always in his native Salina, Leonard said. As an avid outdoorsman, he would travel to Salina every year for the opening of hunting and fishing season until his health prevented him from doing so.

In October, Leonard came to the annual 31ers dinner to help celebrate the legacy her father helped cultivate. She said she and Colby grew closer as the years went by, and he loved telling her old stories of what life was like working on the dam. Although he told them often, Leonard said she never tired of hearing her father take her down memory lane.

“He would tell them over and over. It was just wonderful,” she said. “He learned a lot on that dam.”

Colby was living in an assisted facility in Northern California during October’s 31ers dinner. Still, Leonard said he was excited to hear about her trip to Boulder City, the place where he first found work on the Hoover Dam 83 years ago.

They were able to share his final moments together with a goodnight kiss.

“I do think he knew at that moment it would be our last time together as he passed peacefully at 4:30 a.m. on Wednesday,” Leonard said. “It was just a warm feeling knowing that we had that special relationship and no one was going to take that away.”

Colby will be buried Nov. 22 in Salina. He is survived by his daughter, Cathy, and son, Joseph Darwin Colby Jr., as well as three grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren.

Contact reporter Steven Slivka at sslivka@bouldercityreview.com or at 702-586-9401. Follow @StevenSlivka on Twitter.