Eagle eyes keep bird count accurate

When it comes to counting bald eagles, technology has to take a back seat to good old-fashioned fieldwork. At Lake Mead National Recreation Area, that means biologists, binoculars and boats.

During the annual midwinter bald eagle survey last week, volunteers and National Park Service biologists counted hundreds of eagles and other birds of prey, not to mention burros, cattle and one underwear-clad gentleman searching for a runaway boat.

The survey dates to the 1990s and is part of a national eagle survey that tracks the population and distribution of bald eagles across the country. Bald eagles were listed as endangered in 1967 but have made a substantial comeback.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service now lists it as a species of “least concern” when it comes to conservation.

So why do scientists keep counting?

‘Indicator species’

“A bald eagle and a golden eagle, that would be your indicator species,” said Lake Mead vegetation manager and avid bird-watcher Carrie Norman. “And so if their numbers are declining, that should be an indication to the population that maybe we should start doing something about it.”

Eagles and other raptors at Lake Mead, like hawks, ospreys and falcons, are at the top of the food chain, so if something’s affecting them it’s likely to affect the rest of the environment.

The survey is conducted during the first few weeks of January, which resulted in last year’s count being canceled due to a government shutdown.

But in 2018, the Park Service recorded the highest number of bald eagles seen in five years.

That generated extra interest in this year’s count, which was heightened even further by the fact that water levels at Lake Mead edged higher this year, said Park Service spokesman Jason Lawor, who joined in on the eagle count for the first time.

The research also is important to the long game, Norman said — helping spot trends that can only be caught from compiling and analyzing data over time.

“Climate change or any kind of environmental thing that will happen to an animal or fish or bird, you can’t get that snippet right away,” she said. “You have to get an accumulation of data. You have to get that trend to see what the actual population is doing.”

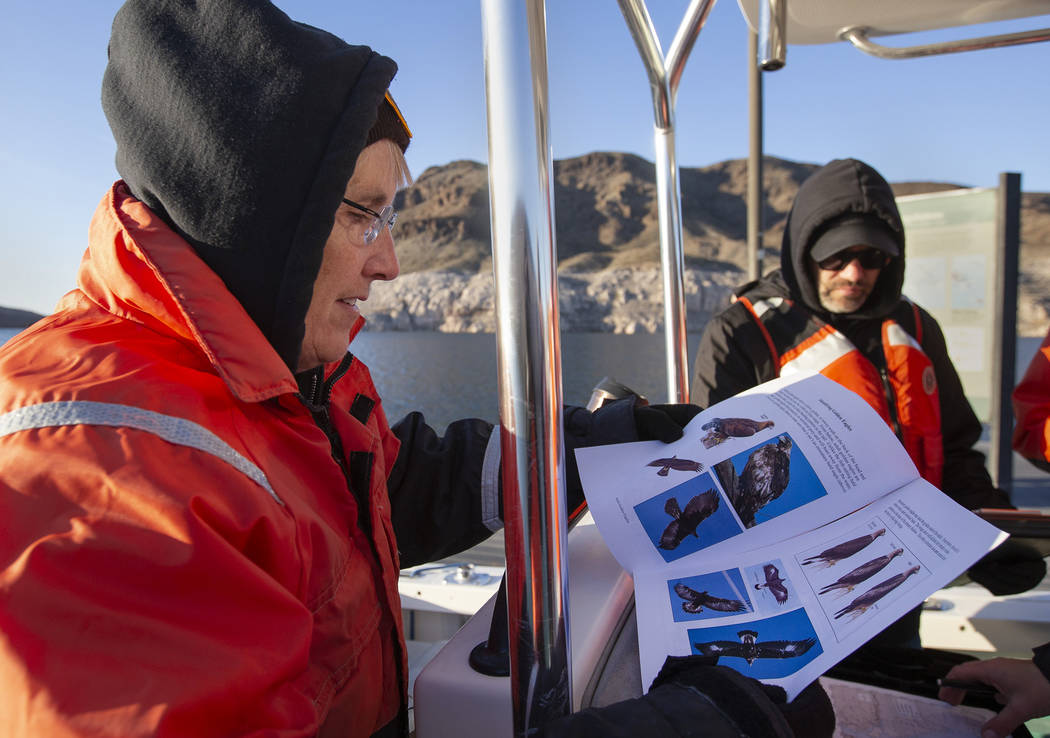

Just as the sun peeked over the horizon the morning of Jan. 15, Norman and a team of shivering Park Service employees and volunteers boarded a boat at Echo Bay.

They’d been scanning the shoreline for less than an hour when Norman spotted the first eagle of the day: a young bald eagle still sporting its mottled white and brown juvenile feathers.

As a veteran of the eagle count, Norman took the lead. Her specialty is plants, but her passion is native birds and she spotted the majority of the birds the group counted.

Just passing through

Eagles and many other birds pass through Lake Mead and Lake Mohave between December and February during their southern sojourn, Norman said.

“It’s a great stopover for food, whether they’re songbirds going out eating berries and that sort of thing, ducks that are getting the vegetation that they’re eating up here or eagles that are catching fish,” Norman said.

It turns out bird-watching is trickier than just watching birds. You have to know their habits, food sources and perching preferences. The rest, Norman says, is practice.

“I don’t know how she sees them,” volunteer Linder Rohrbach said admiringly, squinting through a pair of binoculars. “She’s got those eagle eyes.”

Despite its name, however, the bald eagle survey isn’t entirely about bald eagles. Many species near Lake Mead and Lake Mohave can give biologists clues about the state of the ecosystem.

Norman and her crew also counted ravens, falcons, hawks, burros and cattle. They were on the lookout for ospreys as well, but didn’t spot any this year.

Ravens are common throughout Southern Nevada, but they also serve as an indicator species at Lake Mead. They go after other birds’ eggs, so a higher or lower than normal number of ravens can indicate problems with other avians.

Burros and cattle, which munch on Norman’s specialty — native vegetation — also can affect bird populations.

Between sunup and sundown, the group spotted a total of 31 bald eagles, short of 2018’s total of 40. Final results were still being tabulated Friday, Jan. 17.

They also stopped to help a man who had taken off his pants and waded into the freezing lake waters after his boat floated away. They weren’t the park rangers he was expecting, but they were the park rangers that were there.

“Wow! Saved by the bird survey,” the man exclaimed, laughing as Norman helped direct him through the marshy water before park ranger Alex Swicegood tossed him the line to his boat.

Contact Max Michor at mmichor@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0365.