So where does that RDA money come from?

It wasn’t all about donuts or whether super bright pink is an appropriate color for a building in the historic district. In addition to donuts it was about, well, dollars.

In a meeting where the city council, operating as the redevelopment agency, committed nearly $200,000 in funds to three private businesses, the most important question was asked by Councilwoman Cokie Booth.

“My question would be this on the redevelopment funds; where do these monies come from?”

The short answer is property taxes but it is a lot more complicated than that.

The law

The whole idea of a redevelopment area is enshrined in the Nevada Revised Statutes, Chapter 279, which was first passed in 1959 and has been revised multiple times, most recently in 2013. The law allows cities and counties to declare an area as “blighted”, which is defined by 15 different criteria ranging from poor design to deterioration to disuse to the presence of an abandoned mine.

While the requirements for the declaration of a redevelopment area were tightened up significantly in 2017. Back when the redevelopment area in Boulder City came into being in 1999, the main requirement was just the 75% of the area had to be improved, which legally just means it is not vacant land.

Once the city or other jurisdiction has put together a board of five “qualified electors” from the city (which means registered voters), that board can declare an area as blighted and set up a redevelopment area. In Boulder City, the redevelopment board consists of all five members of the city council.

So, there’s a board and an area, so where does the money come from? Because Boulder City is not able to take on debt of more than $1 million without a vote of the residents, it mostly comes from something called “tax increment financing” (TIF).

The money

Basically, as redevelopment occurs and properties change hands, which results in a new and usually higher total tax (even though the percentage does not change) because the property is reappraised.

So, under TIF, the amount that the property owner paid when the redevelopment area was created continues to go to the same places it always has. But the difference between the original amount and the new, higher amount gets funneled to the redevelopment agency.

The original law says that individual owners of blighted properties need encouragement to improve those properties. In Boulder City, that is done by reimbursing owners for specific work to improve their properties. A property owner can qualify for up to 30% of the costs of upgrading a property within the redevelopment zone. This is how both a very large corporation that owns everything from extended-stay motels to malls and donut shops, and a local church both got a commitment for funding last week.

Crucially, the funding is a reimbursement. The committed money is only disbursed after the work has been completed. So, for example, more than two years ago, after a local couple bought the old Flamingo Inn Motel, they got a commitment from the RDA for reimbursement for planned changes to the exterior of the building. But the work was never started and the property has been sold once and is in escrow again right now (more on this in a future issue). So the funds, though committed, were never actually given out.

The fund

The RDA fund in Boulder City is pretty healthy. According Economic Development Coordinator Raffi Festekjian, the current fund balance is about $4.5 million which, properly invested, should be able to fund a lot of improvements for a long time.

But there is a catch.

The lifespan of a redevelopment area is limited by state law to a period of 30 years. The redevelopment area in Boulder City was established in 1999 so it expires in 2029, just four year from now.

If there is money left in the fund when the expiration dates hits, what happens to it?

It gets sent back to the entities that would have gotten the increase in taxes had the TIF never been implemented. One might think that means it goes to the city but that is not totally right. In fact, it’s about 90% wrong.

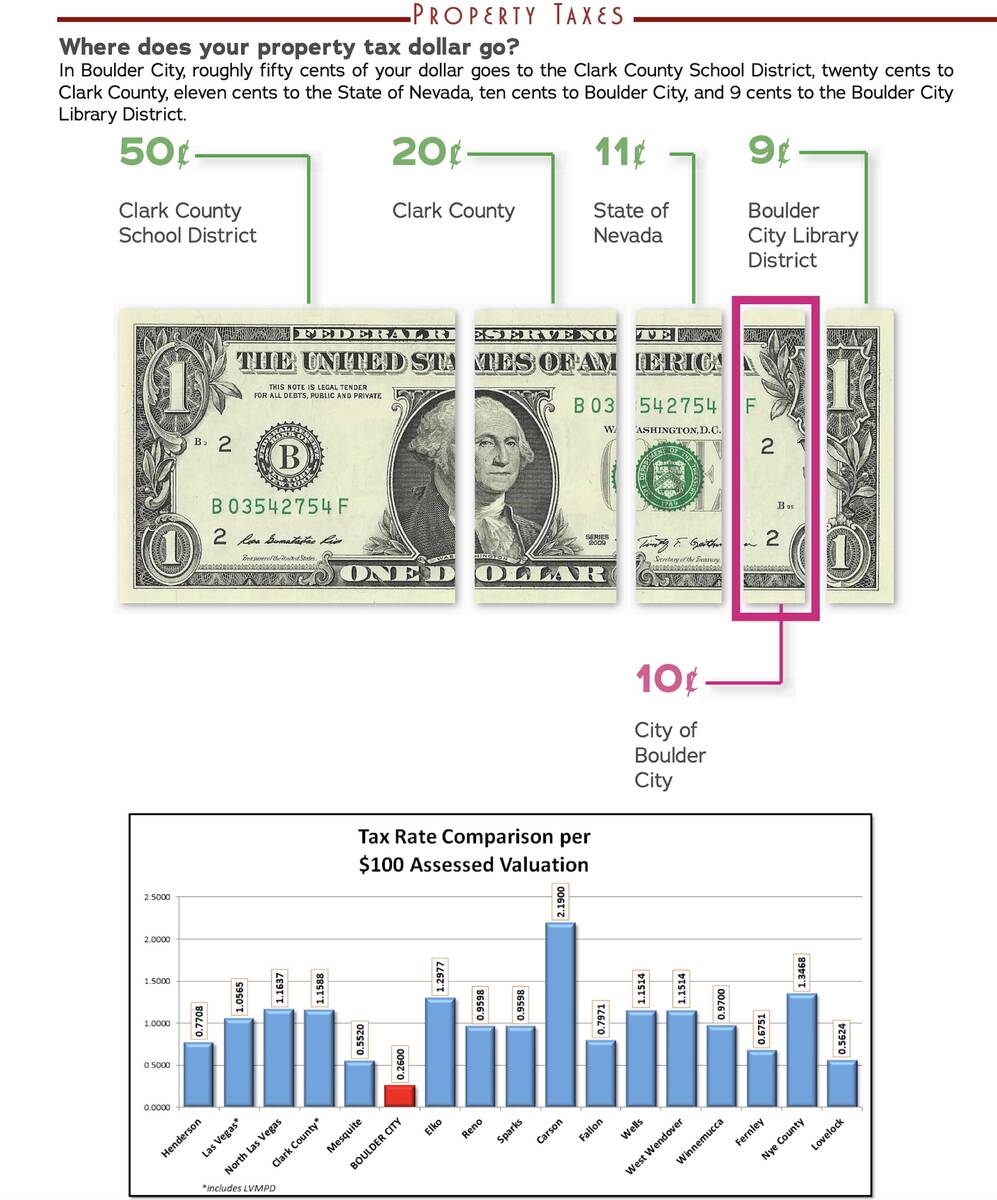

For every dollar of property tax collected in Boulder City, 50 cents goes to Clark County School District, 20 cents goes to Clark County, 11 cents goes to the state and nine cents goes to the Boulder City Library District. Just 10 cents goes to the city.

So, for illustration, if there is $1 million sitting unspent when the expiration comes, of that, $500,000 would go to CCSD, $200,000 would go to the county, $110,000 would go to the state and $90,000 would go to the library. Just $100,000 would go to the city’s general fund.

“So in 2029, whatever remaining funds that exist are dispersed to the taxing bodies that were impacted in 1999 when the taxes were frozen,” said Community Development Director and Acting Deputy City Manager Michael Mays. “And it’s distributed proportionately per the tax rate that’s been in place. So it would go to the school, it would go to the county, etc. Now, the city is looking for ways to utilize those funds before the 2029 expiration.”

Councilwoman Sherri Jorgensen put it into perspective.

“This is 30%, right? So that means someone’s putting in 70% of their money. So, in my mind, as I look at it, it makes sense because if you don’t redevelop, redesign, refresh, then you end up looking at what we see now a little bit, which are some dilapidated buildings.”