Aging dams vulnerable; engineers learn from structural failures

Hoover gets all the glory, but Nevada is home to more than 650 dams, nearly a quarter of which are classified as “high hazard” because of what could happen if they fail.

State records identify 133 dams in Clark County alone, including 67 high-hazard structures, most of them flood detention basins perched above — and built to protect — residential neighborhoods.

Dam safety has been thrust into the national spotlight in recent weeks by the ongoing emergency at California’s Oroville Dam and the Feb. 8 collapse of an earthen dam in northeastern Nevada.

For years, engineers and safety advocates have warned that the nation’s dams are aging and do not receive nearly enough funding for inspection and rehabilitation.

According to the Association of State Dam Safety Officials, a national nonprofit advocacy group, $60.7 billion in repair work is needed at state and locally owned dams across the U.S. More than $18.7 billion of that work is required at high-hazard dams, it says.

Roughly 20 percent of those high-hazard structures do not have emergency plans to protect people and vital infrastructure in the event of a failure, the association says. Nevada is somewhat better off, with less than 10 percent of its high-hazard dams lacking emergency action plans.

A high-hazard rating does not reflect a dam’s condition, but rather its potential for death and destruction in the event of a failure. In other words, it’s a measure of what’s downstream, not whether a dam is structurally sound.

State Engineer Jason King is head of the Nevada Division of Water Resources, which oversees dam safety. He said roughly 90 percent of the high-hazard dams in Nevada are in satisfactory condition, the highest rating state inspectors give.

King said his department doesn’t keep a ranking of the state’s most hazardous dams.

“(But) if we had a top 10 list, I would guess eight or 10 of them are in Las Vegas,” he said.

A POOR REPORT CARD

Many people don’t even re2

alize they live or work downstream from a dam, partly because they don’t understand what a dam really is, safety officials say.

King’s office regulates all structures with an embankment at least 20 feet tall or the ability to impound at least 20 acre-feet — think of a football field covered with 20 feet of water — of “mobile material.” That includes everything from mine tailings or ponds filled with chemical-laden water and sludge to flood detention basins with nothing in them most of the time.

The vast majority of dams in Nevada are made from dirt and rocks, and most are privately owned.

Luke Opperman, a water planning and dam safety engineer for the state, said about a third of Nevada’s dams were built for flood control, a third for mining operations and the remaining third for “everything else.”

The 144 high-hazard dams in Nevada are inspected annually by licensed engineers. Another 113 significant-hazard dams are inspected every three years and about 400 low-hazard dams are inspected every five years.

“And there’s probably another 100 that don’t meet our criteria (for a dam) that we keep an eye on anyway,” King said.

The state relies on just 11 people to conduct inspections, seven of whom are licensed engineers and four of whom work full time for the Division of Water Resources.

In its 2013 national infrastructure report card, the American Society of Civil Engineers gave Nevada’s dams a D+ grade, citing state staffing levels and funding for dam safety at about half of the national average. The same report gave the nation as a whole a D for its dams.

Since then, Nevada has added more inspectors and assigned engineers from other departments to conduct dam checks. Gov. Brian Sandoval’s recommended budget for 2018-19 includes three additional engineers for the water division.

FROM ‘FAIR’ TO FAILURE

Inspections alone do not guarantee safety.

State regulators examined the Twenty-One Mile Dam in northeastern Elko County in late July and did not identify any problems requiring immediate attention. They rated the low-hazard earthen dam in “fair” condition and gave the owner a list of recommended improvements to be made within three years.

On Feb. 8, the agricultural dam gave way amid heavy rain and snowmelt in the area. No one was killed or injured, but floodwaters washed out a section of state Route 233 and left railroad tracks dangling in the air near the Utah state line, about 25 miles away.

Rushing water and damaged roads have so far kept regulators from determining why the remote dam failed.

“We are planning to do an investigation as soon as physically possible,” said Eddy Quaglieri, engineering manager for the state dam safety program.

An inspection letter from last year warned of seepage, debris and plants clogging the spillway and mature vegetation covering and possibly weakening the embankment at Twenty-One Mile Dam.

Then there is the overall age of the structure, which was built in 1929.

“Those old dams are vulnerable,” King said.

STILL STANDING TALL

Luckily, Nevada’s largest and most iconic dam seems to be aging pretty well.

The risk of a failure at Hoover Dam is “very, very low,” according to Nathaniel Gee, dam safety program manager for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation on the lower Colorado River.

The 82-year-old structure undergoes a visual inspection every quarter and a more detailed yearly examination. “It takes almost an entire week to do the annual inspection,” Gee said.

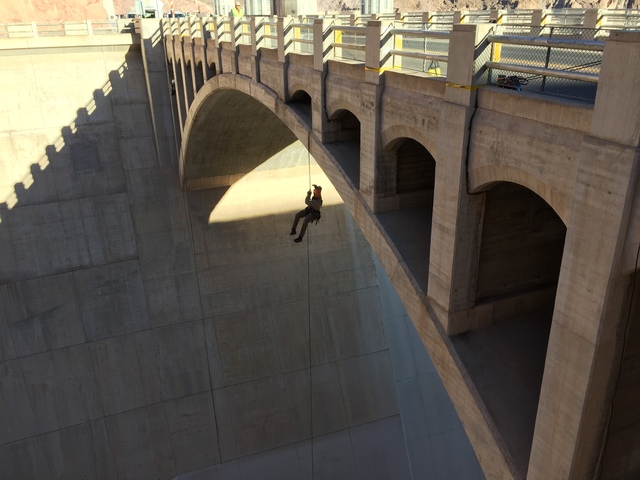

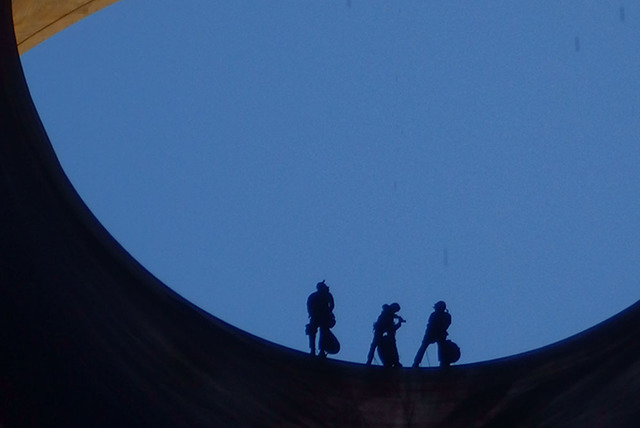

Every four years or so, engineers descend on Black Canyon to go over every inch of the dam. For those reviews, Gee said, inspectors don scuba gear to check submerged portions of the structure and use ropes to rappel into the spillways and penstocks, or floodgates. They also conduct a full risk analysis using updated information about the area’s geology, seismology and hydrology.

Between inspections, the structure is monitored by automated sensors and the human “dam tenders” trained to spot signs of trouble, Gee said.

Hoover certainly saw its share of problems early on.

As Lake Mead was filling for the first time in the late 1930s, sizable leaks began to develop between the dam and the canyon walls, prompting a nine-year drilling operation to seal the faults and fissures.

That work was still underway in 1941 when the lake was intentionally filled to overflowing to test Hoover’s emergency outlets. The water hammered down the spillways with such force that it chewed through the thick concrete lining and into the bedrock underneath.

Subsequent engineering changes improved the performance of the spillways, but the structures were damaged again in 1983, when record flows on the Colorado caused Lake Mead and Lake Powell to overflow. The spillways at Lake Powell’s Glen Canyon Dam sustained severe damage that year.

Gee said that anytime a dam or one of its components fails, it provides lessons that engineers can use in future designs and existing facilities. He expects the industry to learn a lot from what’s been happening at Northern California’s Oroville, the nation’s tallest dam, where the main spillway collapsed and the emergency spillway nearly failed, triggering a mass evacuation downstream on Feb. 12.

Contact Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350. Follow @RefriedBrean on Twitter.