When it comes to establishing courts that hear cases only from military veterans, there are some individuals who take umbrage and feel that veterans should be tried only in traditional courts.

The idea behind veterans courts is that some who have experienced combat return from overseas with specific problems or habits that may lead to activities in civilian life that break the law. The fact that they served the nation honorably and were exposed to negative situations because of their service is something that judges and court systems should take into account when hearing cases or imposing sentences.

When some critics say that veterans should not be tried in special courts, the president of Veterans in Politics, Steve Sanson, has an answer for that: “There are DUI courts, juvenile courts, prostitution courts, all these different types of courts. There are diversionary courts for anger management and for divorce proceedings. Why is it that people are having a problem with veterans courts?”

Besides being involved in political issues, Sanson is a veteran and has seen firsthand the effects of war on soldiers. An active advocate for veterans courts, his organization has special praise for four judges in particular. He said Judge Martin Hastings of Municipal Court, District Court Judge Linda Bell, Justice of the Peace Melanie Tobiason and Chief Judge Mark Stevens of Henderson’s Municipal Court are strong supporters of courts trying to work with veterans who are accused of crimes.

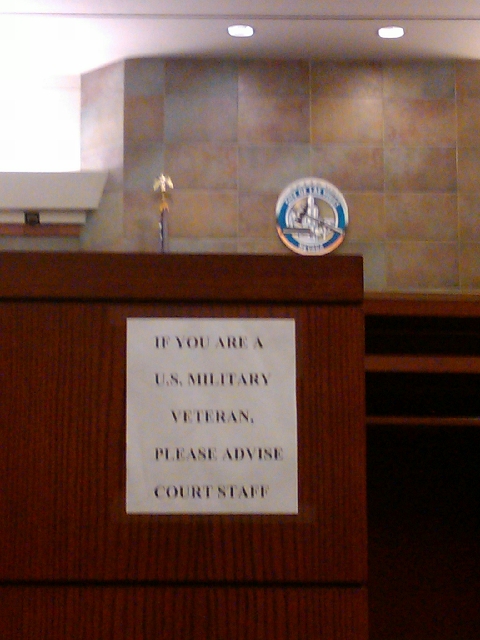

Stevens heads Henderson’s Veterans Treatment Court, an alternative program for veterans charged with misdemeanor crimes while struggling to readjust to civilian life. A Henderson spokesperson pointed out that many such veterans “wrestle with substance abuse and mental illness that appear to be related to military service.” The veterans court focuses on those underlying issues and provides access to resources that enable successful compliance with the courts orders.

Stevens, a Marine Corps veteran, said, “No bond is as strong as the one that exists among those who have fought for their country. Having a fellow veteran to talk to and get their support and guidance helps our defendants successfully complete the program.”

Stevens served in the Marines as a JAG lawyer and company commander. While working in Henderson, he said a public defender happened to stop by his office one day and casually suggested, “I think we should start a veterans treatment court.” Stevens said, “That sounds like a great idea. Two days later we had court, our first couple of veterans.”

And he found the mayor, city council and police department to be very supportive. The veterans court is held at 2 p.m. each Thursday. Some defendants come almost every week as they progress through the system. Some come once every five weeks, depending how well they do in the program.

“We’ve had 20 graduates,” Stevens said. “There are about 40 currently active in the program.”

Stevens noted that the individuals range “from a brigadier general to the lowest ranking, from Vietnam to the current wars. How long they stay is based upon what their issues are. A lot have PTSD, traumatic brain injuries,” he said. “Some have addiction issues related to their service. It depends on what their needs are. Two nurses from the VA come to our court with computers. We have a meeting one hour before court to discuss individuals as to how their treatment is progressing.”

Some veterans go through random drug and alcohol testing. “Sometimes we try to get them into US VETS to get them housing,” Stevens said. “It’s a broad-based approach. These are all misdemeanors. It’s far more intensive if they just decided to accept punishment and go from there. It’s voluntary to be in the program.”

The veterans are often referred from other courts “and we decide whether they’re qualified for our program,” Stevens said. “Some veterans decline and would rather go through the regular court system. They have to want it,” Stevens said. “If they want to turn their life around, this is their opportunity.”

Sanson said veterans courts had already been established in 2009 in Washoe County. But it took until 2011 for Clark County to get off the ground with its own such courts. Sanson said Gov. Jim Gibbons had signed the State Assembly and Senate bills that established veterans courts in Nevada. But until Sanson began to inquire, he said Clark County ignored the law.

Author Brad O’Leary, while not specifically addressing veterans courts in his 2009 book “Shut Up, America!” nonetheless wrote that politicians can maintain power by assuring that their opinions or points of view are the only ones citizens ever hear. By controlling content, citizens can be controlled. So while the law authorizing Nevada veterans courts was passed and was a matter of public record, “Nobody pushed it. That’s why it took so long,” Sanson said.

He said it was his questioning and bringing it to the forefront that led several local courts to finally begin hearing veterans cases with more tolerant viewpoints. He said there are several other examples of politicians not promoting laws that can help veterans, one being recently failed Assembly Bill 271.

“The bill would have brought Nevada law into compliance with federal law and ensure veterans’ rights are followed by state courts,” he said. The bill addressed U.S. Code Title 38, Section 5301(a) that makes veterans disability benefits immune from taxation, claims of creditors, attachment, levy and seizure. The law excludes disability compensation from net disposable income. Yet in Nevada, Sanson said some divorce lawyers are demanding that judges ignore federal law and award such income for alimony. “In many cases, this leaves the veteran in dire financial circumstances, some penniless and homeless.”

In another twist of the law, veterans courts mainly stay with veterans who are charged with misdemeanors. A bill in the Assembly was recently defeated that would have officially opened the courts to veterans charged with violent crimes. Stevens said that even now it’s still possible for such defendants to go through veterans courts, but the prosecutors have to agree that it would be appropriate.

“We don’t allow anyone in the program if the victim of the crime doesn’t want them into the program,” he said. “It tends to be domestic battery cases, like a push, and the prosecutor thinks it’s a good idea based on the circumstances. We’ve had a number, but it’s a situation where PTSD was reacted to. Even if it’s a DUI, if someone is hurt in an accident, all have to agree. The bottom line is that the victim has rights.”

Veterans stay in the court program typically for one year, some longer. “We need to make sure they are on the right track,” Stevens said. “We never want to see them again except as alumni. We use mentors, vets who volunteer their time. They are a guide, role model, a friend.

“One veteran lost his bicycle that he used to get to work. His mentor put a notice on his blog, and a day and a half later the veteran had a new bike. Some mentors might meet them outside, might have lunch or something. Some are retired people, police officers, retired veterans who want to give back. Veterans might not feel comfortable talking to me, but they can talk with mentors.”

Part of the program is funded by the nonprofit Henderson Community Foundation. “Sometimes we buy bus passes,” Stevens said. “People can donate money. We utilize the vets center and VA for help. US VETS also does some (free) testing for us.”

Stevens said that when veterans graduate, they still have those services available. Once they are accustomed to the help, they can continue even when they complete the court program.

Journalist and author Chuck N. Baker is an Army veteran of the Vietnam War and a recipient of the Purple Heart. He is the managing editor and the host of the “Veterans Reporter Radio Show” on KLAV-AM (1230) from 8 to 9 p.m. Thursdays and the “Veterans Reporter News” at

6:30 a.m. Fridays on VEGAStv KTUD-Cable 14.