A proposed energy storage facility got a second bite at the apple last week as the city council voted unanimously to forward a new application for a different and smaller plot of land for the project to the planning commission for possible addition to the city’s land use plan.

Back in June of last year, they voted 4-1 (with Councilman Matt Fox opposed) to approve the beginning stages of changing the land use plan to allow for an energy storage facility that would use no batteries. Fox was opposed due to the location, which he described as too close to areas some of his supporters use for off-highway vehicle recreation.

After that application went to the planning commission and the company —a Canadian outfit called Hydrostor —heard concerns from both the commission and the public about the location, they withdrew that application. They then did their due diligence on a different plot of land that is half the size and a half a mile closer to the I-95 and further from dirt roads and trails used by off-highway vehicle enthusiasts.

This time around, the questions from council members were more about the process of moving dirt than about dirt bikes. Responding to concerns about construction trucks coming into town, a company rep said that they are working with the state on the possibility of constructing a temporary bypass that would allow trucks to go directly from I-11 to I-95 without having to travel on Boulder City Parkway.

If approved, the construction process would take three to four years and employ up to 700 people, first to excavate and then to construct.

The proposed project would be like nothing anyone in Boulder City has ever seen.

To start, a quick review of how electricity is generated in the engineering marvel that is the very reason for the city’s existence —Hoover Dam.

The dam impedes the flow of the Colorado River, turning a former desert valley into a reservoir that is more than 1,200 feet deep when it is full.

As water continues to flow into the area, it enters the dam at near the 900-foot deep mark and becomes something like an enormous indoor waterfall. As the water falls through large pipes to the point near the bottom of the dam where it is released back to the river, it turns giant turbines. An old one of these can be seen in Wilbur Square. The turbines rotate a shaft which, in turn, rotates a series of magnets inside an enclosure of copper coils and the fluctuations in the magnetic field are converted to electricity.

Most electricity generation, including wind, uses the same kind of spinning setup with the difference being what power is used to produce the rotation. Solar is the lone exception here.

As more and more panels, which convert sunlight to electricity, are installed in a valley where the sun shines almost year-round, the point is rapidly coming when the Eldorado Valley will produce more electricity during the day than can be absorbed by the grid. The challenge becomes how to store that “excess production” so that it can be used after the sun goes down.

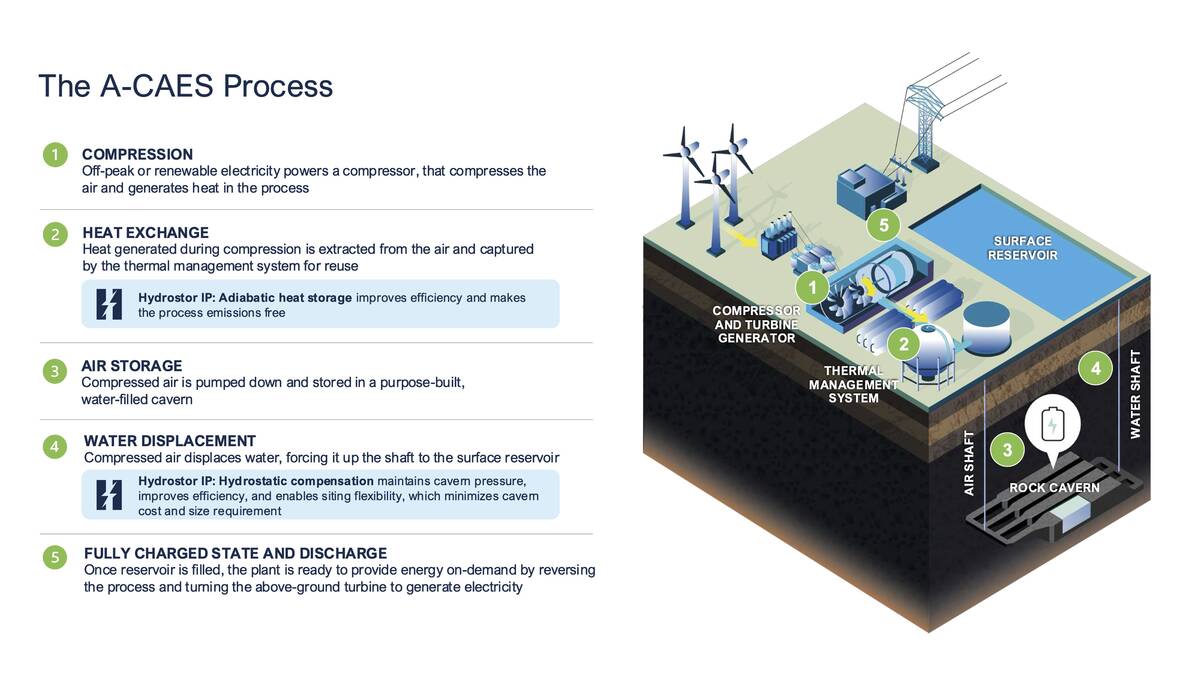

Dean Tuel, Hydrostor’s Vice President of Origination for North America, spoke with the council last summer to explain how the system works. In its most simple form, the technology uses excess solar energy and then the weight of water to compress and then release air in a way that drives the same kind of turbines as in Hoover Dam, except in the middle of the desert.

Hydrostor was co-founded by Curtis VanWalleghem and Cameron Lewis in 2012. Together they came up with the idea for A-CAES technology, or compressed air energy storage.

If the project ends up moving forward, Hydrostor would excavate a large cavern underground in a 300-acre parcel of desert. Above the cavern would be a reservoir as well as turbines that serve a dual purpose.

The cavern would be filled (a “one-time” fill as Tuel put it) with water. During the day, excess solar energy would be used to power the turbines in one direction to compress air and force it into the cavern. The air would be compressed to such a degree that it would force the water to the top and then out of the cavern and into the reservoir. The air compression process would create heat, which is captured and stored to be used later in the process.

At night, when the air is no longer being compressed and pumped into the cavern, the weight of the water would rush back down into the cavern, displacing the air and causing it to flow in the opposite direction, turning the turbines and generating electricity.

In short, it is not actually storing electricity in the form of electrons. It is storing the potential for electricity in the form of pressure and thermal energy potential.

It may sound like science fiction, but the company is already doing this in Canada. Hydrostor’s two mega-watt Goderich facility was commissioned in 2019, and is contracted to Ontario’s Independent Electricity System Operator.

The Goderich facility showcases the capabilities of the technology and provides a foundation for Hydrostor’s other projects, two of which are in late-stage development in California and Australia, and are expected to come online before the end of the decade. In addition to these two projects, Hydrostor has a global pipeline of more than seven gigawatts, which includes the proposed Boulder City project.