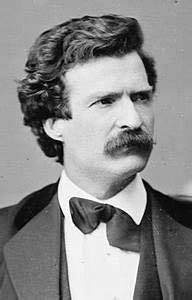

Most everyone likes a story by Mark Twain, or a story that might have Twain himself involved.

Samuel L. Clemens, a Missouri-born, Mississippi River boat pilot and one-time Confederate soldier, came to Nevada in 1861. He didn’t like being a soldier very early in the Civil War, so as he himself claimed, he just deserted. Arriving later in the Nevada Territory, he tried a number of things, including hard-rock mining.

But where he found his real talent was as a newspaper reporter on the Territorial Enterprise in Virginia City. He did rather well there, including creating a pen name for himself: Mark Twain.

Eventually moving to California and sending in a story, “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County,” to New York in 1865 where it would become a national success, Twain and his manager, Dennis McCarthy, later returned for a lecture tour in Nevada. His spoke to packed houses and received standing ovations at each of his several engagements.

Following his final lecture at Gold Hill, Twain and McCarthy decided to walk back to Virginia City. But it was bitter cold that night of Nov. 10, 1865. Not a long walk, but the Arctic winds had dropped the wind-chill factor to near freezing. As the men walked, suddenly out of the dark, several masked men appeared and demanded, “Hands up!” The bandits identified themselves as “Beauregard, Jackson and Sheridan.” At gunpoint they robbed Twain of some cash, two jackknives, some pencils he was usually known to carry, and a prized $300 watch. McCarthy was also robbed. One even pointed a gun a Twain’s head.

Before slipping away into the dark, the robbers told Twain and McCarthy to “stay right where they were, not move for half an hour.” Then they were gone.

Even though it was bitter cold, the men did as they were told, before running to Virginia City and the sheriff to report the crime.

Two days of searching by police failed to turn up the robbers or the stolen property. Twain was furious at this outrage.

As Twain and McCarthy were to leave on the stage to California, friends and well-wishers gathered to say their goodbyes. As they were sitting in the stagecoach waiting to move out, a package was passed to Twain through the open window. Upon opening it, he found all his money, his watch, the knives, the pencils and the masks the robbers had worn in the robbery.

Looking out the window, he looked right into the faces of three men waiting for the stage to leave, who identified themselves as “Beauregard, Jackson and Sheridan,” names of famous generals from the recently ended Civil War. Twain knew instantly these were the men who had robbed him. And what’s more, they were some of his closest friends in the area and they had pulled off a tremendous practical joke on the famous humorist/author.

Better yet, McCarthy had been in on the prank the whole time, too.

But Twain was not at all pleased at this. Witnesses say he turned the air quite blue with curses, (some of which he may have known from his days aboard Mississippi riverboats), leaning out the window, trembling with fury, shaking his fist at nearly anyone.

As the stage pulled away, heading down C Street, the more Twain fumed, the louder the assembled crowd howled with raucous laughter.

Thus was the end of his otherwise triumphant return to the site of his first labors as a newspaper reporter, a man who later became one of the all-time greats, if not the foremost author of American literature and culture.

One of Twain’s biographers, Roy Morris Jr., in his book on Twain’s life, wrote that Twain tried to downplay the incident in some of his later writings, saying, “They did not really frighten me bad enough to make their enjoyment worth the trouble they had taken.”

But Morris also notes one of the pranksters disagreed, saying, “Twain was the scaredest man west of the Mississippi.”

Twain later fired McCarthy as his manager.

The legacy of Twain lives on to this day. Famed author Ernest Hemingway later wrote, “All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain, called ‘Huckleberry Finn.’ There was nothing before. There has been nothing as good since.”

And Hemingway certainly knew of the greatness of another famed American novel: “Gone with the Wind.”

(Adapted from a story by Harold’s Club, 1954, and Roy Morris Jr., 2010.)

Dave Maxwell is a Nevada news reporter with over 35 years in print and broadcast journalism, and greatly interested in early Nevada history. He can be reached at maxwellhe@yahoo.com.