Anson Call, the man who was instrumental in establishing the community of Fort Callville, later just Callville, about seven miles upriver of Black Canyon to serve as a seaport for steamboats going back and forth on the Colorado River, had a vision for something on a more grand scale.

In the late 1850s, it was his firm belief that someday the territory of Southern Nevada would embrace a large settlement of Zionists, converts to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. A few years later, he received an order from church authorities to build a fort at the head of the Colorado River and did it quite well.

Unfortunately for historians, what was Callville now is somewhere under the waters of Lake Mead behind Hoover Dam. But this story is about then, not now.

Historians, such as Don Ashbaugh and others, note that the purpose of Callville was to receive supplies and Mormon proselytes brought upriver from Mexican and California towns. These folk, along with other assorted travelers, adventurers, miners, drifters, gamblers, vagabonds, maybe an outlaw or two, etc., would then have to find other means to head inland and, being resourceful folk as they were, they usually did.

Ashbaugh wrote, “A constant stream of wagon trains carried away the freight, (and passengers) across the long rugged road to the Mormon settlements in other parts of Nevada, lower Utah, and Salt Lake City.”

However, getting a steamboat upriver on the Colorado in those early days was no easy task. The Army had made several, and difficult, attempts to get through the near Category 4 and 5 rapids just below the site of Fort Callville. But the settlers at Callville, although not likely from the Army Corps of Engineers, still had a good plan.

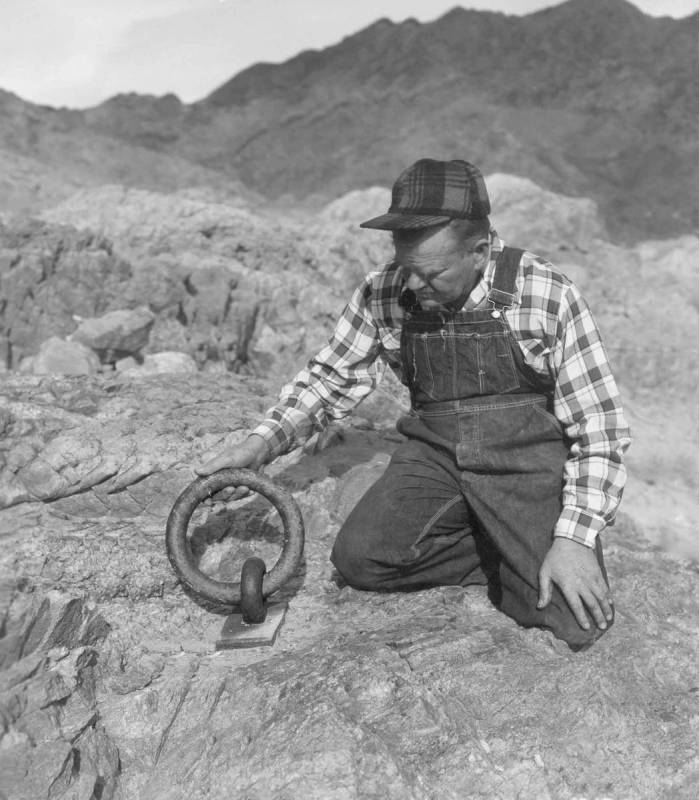

The paddle wheeler Esmeralda, already in service, was fitted with a steam winch on deck as were two other steamboats, the Nina Tilden and the Mohave, that serviced the river approaching Ring Bolt Rapids, an appropriate name. At the rapids, huge 12-inch iron bolts were set into the side of the huge reddish-gray rock at strategic points on the Nevada side of the Colorado, and a heavy cable, the far end of which was attached to a huge boulder, was winched in, helping the large steamer get past the rapids. Any Navy man would have been proud.

Ashbaugh wrote, “Nobody ever recorded, as far as this writer can determine, who the genius was that conceived the method of traversing the rapids of Black Canyon, but the solution was comparatively simple … The cable attached to the ring bolts was picked up by the crew and fastened to the winch. On the upstream haul, the winding capstan assisted the paddle wheel to get through the rapids — on the down trip, the process was reversed with the cable let out slowly and serving as a snubber to prevent the boat from going out of control.”

Historians don’t say if it was a smooth or choppy passage, but it worked. Year-round, too.

Later, other boats added the same equipment and extended their service upriver, even as far as the Virgin River.

The Esmeralda, Nina Tilden and Mohave kept to a fairly regular schedule as the flow of emigrants, supplies and materials to Utah and elsewhere began in more earnest. The ships made regular trips between Yuma, Arizona, upriver over 400 miles to Callville, usually a 3½-day trip one way.

Many of the people and materials from eastern locations and manufacturers had already made the nearly six-month journey around Cape Horn and up the Pacific coast to the Gulf of California.

With the obvious help of the engineering work at Ring Bolt Rapids, navigation on the Colorado flourished until the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, which cut travel time across the U.S. from six months to six days. Water travel was no longer needed, unless desired.

Historians also note that later attempts to increase usage on the river failed when it became impossible to secure federal funding to remove the navigational obstacles.

Still, Ring Bolt Rapids is a good story and testimony to the ingenuity employed by those early settlers of our beloved state, linking Nevada’s wilderness to the outside world. It is but another story of interest to be found in the many colorful pages when you go in search of Nevada’s Yesteryear.

(Adapted from a story by Harold’s Club, 1950, and author Don Ashbaugh, 1963) Dave Maxwell is a Nevada news reporter with over 35 years in print and broadcast journalism, and greatly interested in early Nevada history. He can be reached at maxwellhe@yahoo.com.