Nothing remains to be seen of a plague that once was an indiscriminate killer of one particular Nevada mining community, but you can find it when you go in search of the state’s yesteryear.

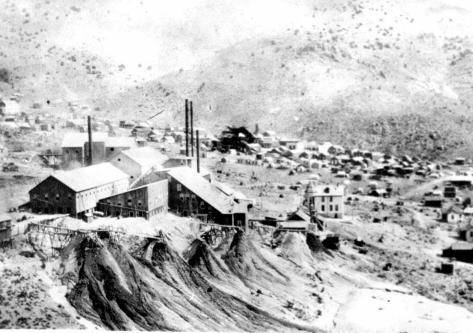

Known often as the “Delamar Dust,” it hung as a light, gray pallor in the tunnels and stamp mill, and spread out over the mining town of Delamar in the mountains of Lincoln County in rural eastern Nevada in the 1890s.

Professor Phillip Earl, formerly of the Nevada Historical Society, wrote in his article on the subject: “Silicosis was a foreign word to the vocabularies of the young farmers who were lured to Nevada, to the thriving camp of Delamar in the mid-nineties.”

Historians, including Earl, note $3 a day was fabulous wage for a young man doing hard rock mining work using power equipment, but with no water. Delamar didn’t have an adequate water source for the mining operations, and what was available was needed mostly for the stamp mill, private homes or domestic use.

Delamar offered cash to men who had grown up on the farm, for example, in St. George, Utah, where they labored 10 to 12 hours a day doing backbreaking work and were barely able to scrape out a living.

Earl writes, “In the mines at Delamar, there was a chance to do better, make a stake, settle down, marry and raise a family.”

By 1896, Capt. Joseph De Lamar’s mill operation was processing up to 260 tons of ore per day and among the richest in the state. Water for the camp was pumped in from a well at Meadow Valley Wash, over the mountain about 14 miles away, but it wasn’t enough. Numerous other mining camps in Nevada had an adequate water supply, but not Delamar.

The gold being taken from the mines there was unique. Geologists noted it was contained in quartzite. To separate the two, the rock had to be crushed, creating large quantities of dust.

Both cemeteries in the ghost town ruins of Delamar display the inscriptions of the many victims of the quartzite dust. The gold-bearing hard quartzite at Delamar, when processed at the stamp mill, produced what some described as the having the appearance of what today would be called smog. It was not as thick or dark in color as can be seen in some major population areas today, but it was there.

Rainfall would clean the air, but only for a time. Rain is not a plentiful commodity in the high desert of rural Nevada.

Also, this light gray cloud was quite different than modern day smog. Earl states it was made up “minute particles of crystalline silica, the main component in sand and rocks like limestone and granite. When inhaled, it can quickly seriously damage the lungs, cause coughing spells and turn into pneumonia.”

Scientists call this silicosis. It is an acute condition characterized by shortness of breath, a lingering cough, weakness, weight loss, fever and bluish skin. It might have been misdiagnosed by doctors in Delamar or in Pioche, the county seat, and labeled as pneumonia or tuberculosis. However, it was much worse.

Without the presence of water to keep the dust down, or the wearing of proper masks, miners, mill workers and townspeople alike were subject to breathing in the crystalline silica. The people did not know what was happening. They most likely felt very confused because not everyone was affected the same way. Mostly it occurred among the miners, but not always.

A 2008 article by the National Academy of Science noted, “When small silica dust particles are inhaled, they become embedded deeply into the tiny air sacs and ducts of the lungs, where oxygen and carbon dioxide gases are exchanged. Thus, the lungs cannot clear out the dust by mucous or coughing.” Inflammation then occurs.

This was happening often to miners coming to work day after day in the mines and stamp mill in Delamar. And many soon found out the devastating results.

Many miners who came also brought young wives and, numerous times, even within a year of arriving, the husband had died of silicosis, without he or his wife knowing what the real cause of death was. The dust was soon given the dubious name “The Widow Maker.”

Many a couple, and their friends, were at a loss to understand what was taking place or what to do about it. Death is no respecter of persons, and Earl writes that, “Death did not stop only with the miners. From miners up through the mill workers, even to the superintendents, Delamar Dust continued to take its toll. Black dresses for women became a style imposed by the necessity of attending funerals.”

He notes further that, “the town’s population at one time numbered between five and six hundred widows of St. George men who had come to work in the mines.”

He doesn’t mention how many came from other places, states or even from foreign countries, Austria in particular.

When De Lamar sold his interests and properties in the town to a group of Eastern investors in 1902, the new owners recognized the problem that De Lamar had seemed uninterested in fixing and brought in more water and abolished dry mining.

“The new method stamped out death from the dust,” Earl writes, “but in the short preceding years, the cemetery had grown measurably and Delamar had established its reputation, known the world over… as the ‘Maker of Widows.’”

After the turn of the century, even though the silicosis problem was corrected, gold production slowed and by 1910, the mill closed and many of the people moved to the new boomtowns of Tonopah and Goldfield, 200 miles to the west.

More than $15 million worth of gold came out of Delamar between 1892 and 1909.

In 1929, there was a bit of a revival when production began again, but the Great Depression came along and production slowed again, and by 1934 the town was abandoned.

Now, Delamar is just ruins. No one goes there except those interested in history and roaming through ghost towns. Only echoes of the past remain among what once was the grand town of Delamar. Yet, it is still a part of the colorful history of the Old West when you go in search of Nevada’s yesteryear.

(Adapted from a story by Harold’s Club, 1948, and Phillip Earl, “This Was Nevada,” 1986)

Dave Maxwell is a Nevada news reporter with over 35 years in print and broadcast journalism, and greatly interested in early Nevada history. He can be reached at maxwellhe@yahoo.com.