Author keeps city from being forgotten

Before Huntington Beach, Calif., was ever a destination for beach bums, surfers and bad TV shows, it was a rural, farm town that didn’t have much going on.

When Japanese immigrants began settling there in the late 1800s, they started a community known as Wintersburg, a place that was all but forgotten until Boulder City-raised author Mary Adams Urashima brought its history to life.

For nearly 50 years, Japanese-Americans in Huntington Beach tried to assimilate to life in the U.S. while trying to overcome racism and bigotry. After President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order No. 9066 in 1942 that forced the relocation of all Japanese-Americans from “military areas” to internment camps, the entire Japanese population in Wintersburg was gone.

Urashima, who moved to Huntington Beach in the 1980s, spent years uncovering their history and how they left their mark on what is now an urbanized Huntington Beach.

“One day I was stopped in traffic and saw this little building. It was a Japanese Presbyterian church from 1934,” Urashima said. “And I remember thinking, ‘Wow there’s a story there.’”

After doing some research and compiling facts about the six buildings she surveyed on the 5 acres, Urashima created a blog dedicated to historical Wintersburg in February 2012.

The blog soon got the attention of the Huntington Beach City Council, who created the Historic Wintersburg Preservation Task Force and tabbed Urashima as its chairwoman.

“I began asking other historians if anybody was trying to preserve the property, but they really didn’t know much about it,” she said. “I reached the point that if something was going to be done, I was going to have to do it.”

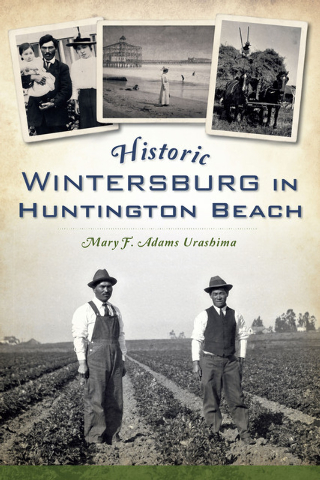

Urashima spent nearly three years researching the material for her book, “Historic Wintersburg in Huntington Beach,” which was published in March by The History Press.

After graduating from Boulder City High School in 1978, Urashima double-majored in news editorial and photography at Northern Arizona University. She moved to Huntington Beach in the 1980s and runs a consulting business that handles government and public affairs. Her 20-year-old son, Keane, studies pre-med at the University of Arizona.

Urashima’s childhood in Boulder City helped inspire her love of history and she wanted to share her thoughts on the book with local residents.

What is your book about?

It’s an intro to the history of Wintersburg Village, which is now part of Huntington Beach. It was the heart of the Japanese-immigrant community in the 1800s, and the book shares some of the history of the Japanese-Americans’ arrival from the late-1800s to the post-World War II era.

Part of the book was to help save six historical buildings from demolition in the 5-acre area. All six buildings represent a big development of Orange County. These buildings they had are extremely rare, not just for California, but for America. Historical Wintersburg is now nominated for one of America’s 11 most endangered places.

The fact that this property survived the urbanization of Orange County is a miracle.

What are the alien land laws the Japanese had to deal with when they came to California?

These laws were specifically aimed at Japanese immigrants and it prevented them from gaining land ownership and citizenship. California passed its first alien land law in 1913.

What made you want to write this book?

To make sure this history is not forgotten. One of the most common reactions I get is, “I had no idea about this.” There’s really a lot of growing interest and affection in this growing property.

How many people did you interview during the process?

Countless. One of the things I was fortunate to find is that in the 1970s and ’80s there was an effort by the history staff at (California State University), Fullerton to collect oral histories from the older Japanese-Americans. They collected them and tucked them away, and I was able to take those oral histories and find bits and pieces and research from there.

How did the Japanese assimilate to American life when they first came to Wintersburg?

They embraced life in America. It was very much a pioneer spirit here because this was a very rural area. Like every other pioneer, they had to create their own lives, build their own houses, make their own farming tools and grow their own food. But they still participated in American life.

The Japanese-Americans from Wintersburg orchestrated one of the very first Fourth of July parades in Huntington Beach in 1905. There was significant interaction and they would invite the community to their events, like when they celebrated the Japanese emperor’s birthday.

It was a very diverse community and people were very much a part of their celebrations. The first Japanese-American mayor in the United States attended the mission in Historic Wintersburg.

What about the reoccurring theme of goldfish farms throughout the book?

There were three goldfish farms in Wintersburg when there were maybe a dozen across the country. It was very unique enterprise, and at one time the area was covered with goldfish.

People were enjoying them as pets and using them as commerce, and it was something that was easily farmed in Wintersburg because of the climate. Goldfish farming was also popular in Asia so there was a familiarity with it.

Which part of the internment process during World War II did you find to be the most disturbing?

One of the traumatic aspects was that some of the Japanese-Americans living there had been there for more than four decades. And the fact that even thought some were American citizens, it still did not protect them from confinement. It’s not something that goes away within a generation or two, and the residual effects are still with us today.

One of the interesting things is that the political push for confinement came from the more urban areas like Northern California because Southern California was still developing.

In farm country, people knew their neighbors. People knew that their friends and neighbors were not responsible for Pearl Harbor, and knew that they weren’t spies. They were traumatized by seeing their friends being forced to confinement.

What about your Boulder City roots?

My family moved to Boulder City when I was in kindergarten. I went to elementary school in the building that is now City Hall. I graduated from Boulder City High School in 1978 and I played clarinet in the band, was on the debate team, the swim team and volleyball team. I wasn’t a star athlete, but I was involved.

How did living in Boulder City help you write this book?

Boulder City had about 6,000 people around the time I was growing up, and I have really great memories here.

Boulder City and my parents (Paul and Barbara Adams) got me interested in history because Boulder City is a historic town. I met a lot of people whose family helped build the dam and I heard their stories, and I think that has a lot to do with how I write history today.